Literary bohemians were associated in the French imagination with roving Romani people (called Bohémiens because they were believed to have arrived from Bohemia[4][5]), outsiders apart from conventional society and untroubled by its disapproval. The term carries a connotation of arcane enlightenment (the opposite of Philistines), and carries a less frequently intended, pejorative connotation of carelessness about personal hygiene and marital fidelity.

The title character in Carmen (1876), a French opera set in the Spanish city of Seville, is referred to as a “bohémienne” in Meilhac and Halévy’s libretto. Her signature aria declares love itself to be a “gypsy child” (enfant de Bohême), going where it pleases and obeying no laws.

The term bohemian has come to be very commonly accepted in our day as the description of a certain kind of literary gypsy, no matter in what language he speaks, or what city he inhabits …. A Bohemian is simply an artist or “littérateur” who, consciously or unconsciously, secedes from conventionality in life and in art.— Westminster Review, 1862 [4])

Henri Murger‘s collection of short stories “Scènes de la Vie de Bohème” (“Scenes of Bohemian Life”), published in 1845, was written to glorify and legitimize Bohemia.[6] Murger’s collection formed the basis of Giacomo Puccini‘s opera La bohème (1896).

In England, bohemian in this sense initially was popularised in William Makepeace Thackeray‘s novel, Vanity Fair, published in 1848. Public perceptions of the alternative lifestyles supposedly led by artists were further molded by George du Maurier‘s romanticized best-selling novel of Bohemian culture Trilby (1894). The novel outlines the fortunes of three expatriate English artists, their Irish model, and two colourful Central European musicians, in the artist quarter of Paris.

In Spanish literature, the Bohemian impulse can be seen in Ramón del Valle-Inclán‘s play Luces de Bohemia (Bohemian Lights), published in 1920.

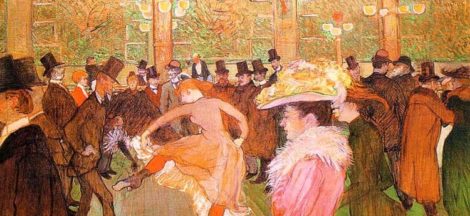

In his song La Bohème, Charles Aznavour described the Bohemian lifestyle in Montmartre. The film Moulin Rouge! (2001) also reflects the Bohemian lifestyle in Montmartre at the turn of the 20th century.

In the 1850s, aesthetic bohemians began arriving in the United States.[7] In New York City in 1857, a group of 15 to 20 young, cultured journalists flourished as self-described bohemians until the American Civil War began in 1861.[8] This group gathered at a German bar on Broadway called Pfaff’s beer cellar.[9] Members included their leader Henry Clapp, Jr., Walt Whitman, Fitz Hugh Ludlow, and actress Adah Isaacs Menken.[9]

Similar groups in other cities were broken up as well by the Civil War and reporters spread out to report on the conflict. During the war, correspondents began to assume the title bohemian, and newspapermen in general took up the moniker. Bohemian became synonymous with newspaper writer.[8] In 1866, war correspondent Junius Henri Browne, who wrote for the New York Tribune and Harper’s Magazine, described bohemian journalists such as he was, as well as the few carefree women and lighthearted men he encountered during the war years.[10]

San Francisco journalist Bret Harte first wrote as “The Bohemian” in The Golden Era in 1861, with this persona taking part in many satirical doings, the lot published in his book Bohemian Papers in 1867. Harte wrote, “Bohemia has never been located geographically, but any clear day when the sun is going down, if you mount Telegraph Hill, you shall see its pleasant valleys and cloud-capped hills glittering in the West …”[11]

Mark Twain included himself and Charles Warren Stoddard in the bohemian category in 1867.[8] By 1872, when a group of journalists and artists who gathered regularly for cultural pursuits in San Francisco were casting about for a name, the term bohemian became the main choice, and the Bohemian Club was born.[12] Club members who were established and successful, pillars of their community, respectable family men, redefined their own form of bohemianism to include people like them who were bons vivants, sportsmen, and appreciators of the fine arts.[11] Club member and poet George Sterling responded to this redefinition:

Any good mixer of convivial habits considers he has a right to be called a bohemian. But that is not a valid claim. There are two elements, at least, that are essential to Bohemianism. The first is devotion or addiction to one or more of the Seven Arts; the other is poverty. Other factors suggest themselves: for instance, I like to think of my Bohemians as young, as radical in their outlook on art and life; as unconventional, and, though this is debatable, as dwellers in a city large enough to have the somewhat cruel atmosphere of all great cities).

Parry -2005

A Paris street – set design for Act II of La bohème

A Paris street – set design for Act II of La bohème